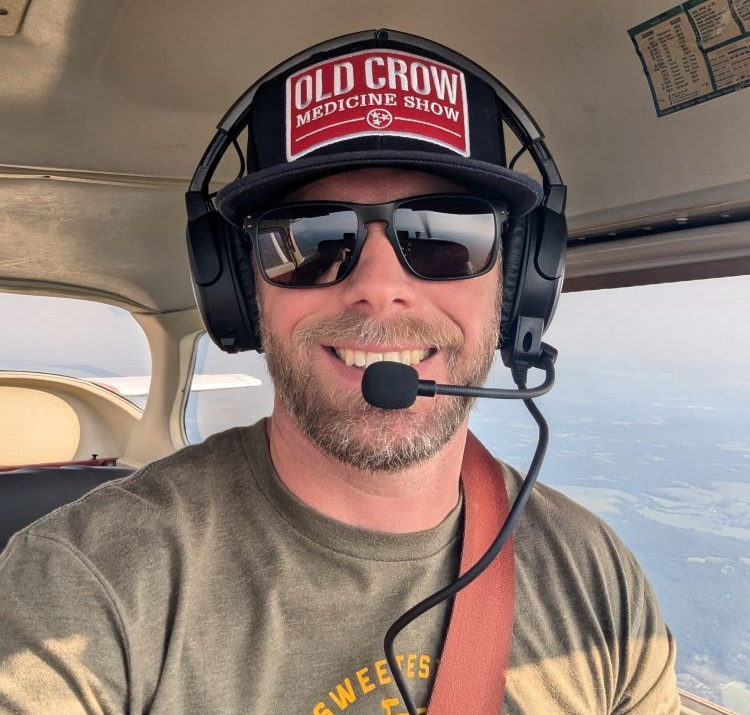

John Sowles

John Sowles of North Yarmouth, Maine has been fascinated with both powered and non-powered aviation since youth. His dad was a Naval aviator in WWII, and the interest rubbed off on John. He joined the Pittsburgh Soaring Club during college and solo’d. He earned his private pilot license, and to fulfill his penchant for old taildraggers he bought a Champ. With supervision from an A&P, he stripped and recovered it over a couple of years. “I needed something to fly in the interim, so I bought a pretty sad looking and crooked TaylorCraft. We ran a plumb line from its cockpit to tail. It was clear that it was bent,” he says. “It was so wild on rollout that my A&P would run for cover every time I came in to land.” It became another three-year project, but when he was finished, John says, “It flew hands off.”

Summers during college he worked for Maine Fish and Game and loved the remote waterways he surveyed. Later, when he was assigned to collect water samples, it was obvious a float plane provided enormous advantage over hours bouncing along in a state pickup truck towing a boat. He used his float rating to cover more lakes in less time more economically and efficiently.

He got his Master’s degree from Auburn University in Alabama, having selected that school for its international fisheries program. With a driving passion to make a difference, he gladly answered the call when the Peace Corps needed someone with academic training in water quality to join their crew in Peru. “I was their translator and guide,” he says. Living at 12,000 feet elevation, his work inventorying high mountain lakes often put him above 16,000 feet with no oxygen, “which seemed to be my physiological limit. The villagers tried to get me to play soccer, but I didn’t do so well.” Some Auburn staff became seriously ill at that altitude and had to be evacuated. “By one in the morning, we realized they needed to be lowered and given oxygen.”

His assignment from Lima to Lake Titicaca was before development. People were isolated. There were very few vehicles on the steep switchbacked donkey paths. “Our chauffeur-mechanic would do major engine repair on our Land Rover in the middle of nowhere,” he said. “Once we were mistaken for the dentist who visits villages once in two years.”

The political crisis forced his crew out, and they were given 24 hours to leave the country. “I was very sorry to have to leave,” he said. He had met Sylvia, a native Peruvian. They continued their correspondence for two years, eventually married in Lima and moved to Maine where he continued his water quality profession and she worked for LL Bean until retiring.

In order to fly together with luggage, John bought a Cessna 170. One nor’easter was so intense, a plane on the ramp broke loose and lifted over the next plane, landing on John’s. “I was underinsured, and I almost gave up. My wife, thank God, said ‘You’ve got to get back into it.’” So he located another 170 in Enterprise, Oregon. He flew it back to Maine, picking up his pilot son in Idaho. The silver lining to the saga was a great view of these United States.

He still owns and enjoys the 170, Champ and the TCraft. “I love old taildraggers,” he admits with typical Maine modesty. The Champ is fit with skis, so John flies all year, bundled up accordingly. He’s working on his instrument rating as of this writing.

John became a trustee for The Nature Conservancy, a post he enjoyed for ten years. He continues to do volunteer work for TNC. “I help with the Water Fund program to protect source water. We work with farmers and communities in upper watersheds, to protect water quality.”

John’s interests in flying and meaningful scientific work rubbed off on their two grown children, as well. Their daughter is a river restoration biologist now serving near the old mining city of Butte, Montana; and their son flew for local Penobscot Island Air. He found work flying floats in Florida in winter, and summers in Michigan flying amphib 206s and Beavers. This coming summer, he will be flying turbine Otters on floats in Alaska.

John retired from his scientific profession, but still consults, currently in the Dominica Republic, spending ten days a year there. He coaches a dozen students, university professors, mining technicians and so forth, who have academic training, but little field experience. He also shares his experience in Kenya so they can use data to make sound decisions. “I’ll continue doing this,” he says. ”I get a lot out of it, and have made a lot of good friends. They impress me with what they can do with limited resources and their commitment to their mission. It gives me a lot of hope.”

Submitted January 15, 2024.

By Carmine Mowbray

Recent Posts